Luckily, there are (still) people in Chicago who think that the arts are important enough to sponsor events for the museums (Free Winter Weekdays at AIC!). Also, luckily, I work down the street for the museum. Consequently, I have been spending many of my lunch breaks feasting on the art work there. Today, I aimlessly wandered into the lower level Textile Galleries, as I was internally outraged that I had not yet discovered them. (check out some of the works here)

I felt an instant connection with many of these pieces and their connections to the abstract works of the mid 20th century.

Designed and executed by Ethel Stein

American, born 1917

United States, New York, Croton-on-Hudson

Five Panels, 1982

American, born 1917

United States, New York, Croton-on-Hudson

Five Panels, 1982

Honestly, it's like Sol Le Witt

and MC Escher

gave birth to Ethel Stein's work. Although, obviously that didn't happen. It's pretty incredible to look at how she can be a link between the work of two artists I have never considered comparing.

Lenore Tawney is another artist whose work captivated me. Her piece "The Bride has Entered" is almost a proto-Kiki Smith.

Hanging Entitled "The Bride Has Entered", 1982

Cotton, plain weave; painted with pigment and gold leaf; attached linen threads in grid pattern

176.5 x 177.6 x 213.3 cm (69 1/2 x 69 7/8 x 84 in.)

I wish I had a better photograph of this. However, when I saw it down the hallway, it appeared as a jellyfish, suspended in the gallery. As I approached it, it appeared to me almost flesh-like in its color and form, almost menstrual. Yeah, yeah, I took it there. Anyway, Kiki Smith always does a splendid job addressing issues of womanhood with elegance the way that Tawney has in this piece.

I'm really excited to look at the work of Lenore Tawney more, as I learned briefly this afternoon that she's a Chicago artist. Maybe I'll have to start working on a post about her soon!

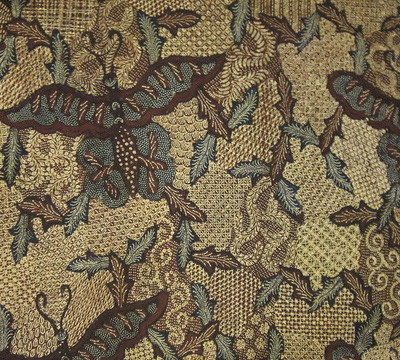

Finally, I spotted this one across the gallery as well

Hanging Entitled "La Mattinata" (Morning Song), 1975

Linen, plain weave; underlaid with cotton, plain weave; embroidered with linen, silk, and cotton in padded satin, satin and stem stitches; laid work and couching

184.1 x 154.3 cm (72 1/2 x 60 3/4 in.)

Maybe I'm the only person in the world who feels this way, but immediately, I felt that this piece has a strong connection to two other artists I have never before compared. It seems to have referenced a famous painting also housed in the same building...

Mary Cassatt

American, 1844-1926

The Child's Bath, 1893

American, 1844-1926

The Child's Bath, 1893

The composition of the piece by Lissy Funk feels so much like the composition of Cassatt's piece as well. Funk almost has the basin at the bottom of her textile! Additionally, the colors are very similar. However, it's not completely Cassatt, but also a little bit Klimt based on the entwining figures: